The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) has strict rules governing the use of ratepayer funds. To avoid the trap of paying incentives to "free riders" or people who would have made an upgrade anyway, they have put in place a rule that says, if a consumer would have done something anyway, they are not eligible for a rebate. Sounds reasonable...

However, in the real world, this rule means that any upgrade that is, say, a replacement of a broken furnace or water heater, can only get an incentive from current code, to whatever level the new equipment efficiency exceeds that number (rather than efficiency gained from what was previously in place, to the new equipment the consumer is buying).

"Pre-existing equipment baselines are only used in cases where there is clear evidence the program has induced the replacement rather than merely caused an increase in efficiency in a replacement that would have occurred in the

absence of the program. " (CPUC Decision 11-07-030, July 14, 2011)

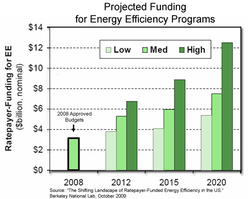

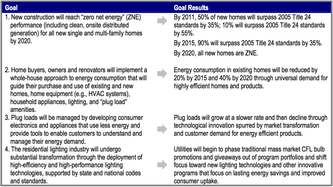

The rub is that it is basically universally understood that if we hope to hit our energy efficiency goals, which in California (brace yourself) is a reduction of energy consumption in existing residential buildings of 40% (and by 2020), the only path to get even close is to harness the billion every year spent on equipment replacement in the reactive markets. Standing up an industry that is proactive is great, but at this point we have basically proven that it is going to be a slow long slog to get there.

First, we are setting up a system that by design gives less incentive to replacement systems and drastically limits what can be deemed cost effective and access utility ratepayer funds. We are asking the HVAC and other energy efficiency industry to change the ways they do business, but we are massively reducing the payoff for doing so. Not a great recipe if we need massive change, and fast.

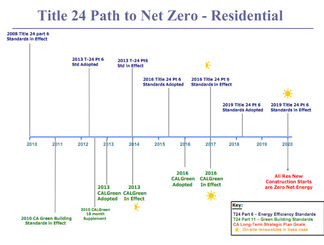

To make matters worse, we have the California Energy Commission (CEC), also attempting to fulfill the very same CA Energy Efficiency Strategic Plan goal of a 40% reduction, has been steadily ratcheting up HVAC and other code requirements. While this is potentially great for what new construction we still have, it does not help us reach the 13.8MM existing CA homes.

CA Long Term EE Strategic Plan Residential Goals

CA Long Term EE Strategic Plan Residential Goals Energy code was originally designed as a minimum standard. In 1978 when Title 24 was implemented in California, it left plenty of room for ratepayer incentives to encourage consumers to adopt greater efficiency measures. Today, however, code has reached a level where it has changed from being a base for the market, into a stick that attempts to push the market towards ever deep savings goals, leaving little room for incentives and carrots. Of course, when code vastly exceeds the market, rather than moving us forward we instead see very low level of adoption. California has what must be the most stringent HVAC change-out codes in the country, however, instead of seeing very efficiency HVAC systems being installed, we see compliance rates that are generally understood to be less than 10% of installed system.

Current CPUC programs actually specify that "The IOU programs seek to enroll customers through a targeted marketing approach that focuses on high energy use homes built pre-1978 (the year that Title 24, California’s building code on energy efficiency, was instituted)." (View PDF) Now clearly there is a problem if we are attempting to target buildings that are farthest from code and represent the most savings potential, which of course is very logical, however those same homes, when code baseline is applied, will not be able to achieve current code and therefor wont receive incentives even with a deep energy efficiency retrofits.

The balance of push and pull has broken down, and we are in danger of turning energy efficiency into tax on building owners where many of the key public and ratepayer benefits accrue without compensation to the utilities and to achieve the public good. While setting a code baseline floor for ratepayer incentives might have made sense in a 1978 world before any minimum standards, it simply no longer allows us to reach our goals.

If we can afford to purchase energy in the absence of energy efficiency, we can afford to use equivalent funds to incentivize energy savings that are 100% clean, and represent a less expensive resource than generation.

This issue represents yet another clear case of the energy efficiency community building barriers and undermining our own efforts, and a reason we need to start unwinding this web of regulation and let data and performance rule the day.

So, in a nutshell, the more we ratchet up code, with a goal of getting to netzero, the less ratepayer dollars will be available to pay for the investment required to get there. In the current model we cannot simultaneously use code to achieve zero energy while tying consumers incentives to the ever shrinking delta between code requirements and the realities of existing buildings. We must move away from this regulatory paradigm towards energy efficiency as a resource where we acknowledge that every BTU and kWh we save is one less we have to generate, and therefor has a value we should reward, regardless of code baseline.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed